On 6 May 2025, the UK’s Department for Business and Trade confirmed that an agreement has been reached on a new trade deal between the UK and India.

The Department for Business and Trade estimates that the deal will increase bilateral trade by £25.5 billion, add £4.8bn annually to the UK’s economy, and boost wages by £2.2bn each year in the long run. This, it says is ‘the best deal that any country has ever agreed with India’.

In 2024, India was the UK’s 12th largest trading partner, with total trade worth £43bn. India has also recently risen to become the fifth-largest economy in the world, and is expected to grow to the third-largest by 2028, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

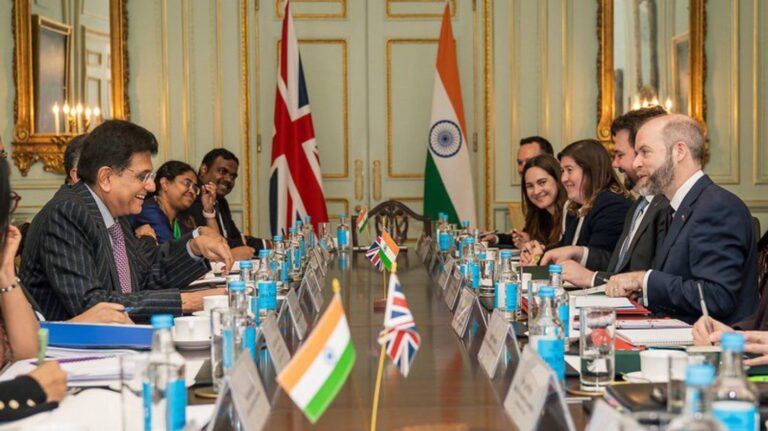

It was confirmed on 24 February 2025 that negotiations towards a trade deal between the UK and India had been resumed. This was after the previous UK government entered negotiations with India in 2022, but no agreement was reached.

With a deal now having been agreed, Jonathan Reynolds MP, UK secretary of state for the Department for Business and Trade, wrote in a post on social media platform X: “Our landmark agreement with India is the largest ever trade deal secured by the UK. This deal will help deliver our Plan for Change, putting more money in working people’s pockets, boosting our economy and bolstering British business.”

And speaking today [7 May 2025] in the House of Commons during Prime Minister’s Questions, UK prime minister Sir Keir Starmer said: “The landmark deal we’ve secured with India is a huge win for working people in this country. After years of negotiation, this government has delivered in months. Slashing tariffs, boosting wages, unleashing opportunities for UK businesses – it’s the biggest trade deal the UK has delivered since we left the EU.”

The agreement is set to enter into force ‘following signature, and subject to fulfilment of both countries’ governmental requirements, including UK parliamentary procedure’.

So what’s involved in this Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and what does it mean for supply chains? There are a number of ways in which UK businesses, and supply chain operations, might be affected.

Tariff reductions

As part of the agreement, tariffs on the import of some goods from the UK to India will be removed or reduced on ‘90% tariff lines, which will cover 92% of existing goods imports from the UK’. Some of the products that are set to benefit from tariff reductions include cosmetics, whiskey, gin, soft drinks and lamb.

Imports of UK-produced whiskey to India, for example, are currently valued at over £200m per year. The current tariff on whiskey imports from the UK is set at 150%, but this will drop to 75% once the deal comes into force, and then reduced gradually over a 10-year period to 40%.

The UK government claims that these changes will result in an overall tariff reduction ‘worth over £400m, which will more than double to around £900m after 10 years’.

Furthermore, UK car manufacturers will benefit from a quota that reduces tariffs from over 100% to 10%. To begin with, this reduction will be applied to internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, but is set to transition to electric vehicles (EVs) at a later date.

Similarly, Indian access to the UK market for EVs and hybrid vehicles will also be staged and under a quota, in an effort to ‘support the UK automotive industry’s transition to fully EV production, while increasing consumer choice’.

As soon as the deal comes into force, 64% of tariff lines will be eligible for tariff-free imports into India, covering £1.9bn of current UK exports to India. This will include UK exports of advanced manufacturing such as aircraft parts and scientific and technical measuring instruments.

After staging over 10 years, the government says ‘the agreement will mean 85% tariff lines and 66% of existing Indian imports from the UK will be eligible for tariff-free entry into India’.

Tariffs will also be eliminated on 99% of Indian goods imported to the UK.

Streamlined customs procedures

On top of increased market access for goods and services exports, the new deal promises to ‘make it easier for UK businesses to trade with and in the Indian market’.

The UK Department for Business and Trade says that ‘faster processing at customs, reductions in technical barriers to trade, agreements to recognise and facilitate digital systems and paperless trade, and reaffirmations of standards in areas like sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) will all contribute to increased trade openness and facilitation while protecting UK standards and providing greater certainty for exporters’.

It is also expected to support collaboration between the two countries, including on new technologies in areas such as agriculture, health, advanced manufacturing and clean energy.

Criticism of the UK-India trade deal

Although the UK government has claimed this deal to be the ‘best deal’ ever agreed with India, it has faced some criticism. Opposition parties have raised concerns about the impact of a Double Contributions Convention (DCC) on UK workers.

The deal extends an exemption on national insurance contributions from Indian workers on short-term visas in the UK, and vice versa, from one to three years. The result is that, during this period, these workers will only make social security payments in their home country.

The government says that the DCC it has agreed to negotiate with India alongside the FTA will ‘support business and trade by ensuring that employees moving between the UK and India, and their employers, will only be liable to pay social security contributions in one country at a time’.

But some have expressed concern that this could lead to a situation whereby employing Indian workers is cheaper than employing UK citizens, especially given the recent increase in employer National Insurance contributions.

Leader of the opposition, Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch MP, told the press: “I had this deal on the table when I was trade secretary and I refused to sign it because that double taxation agreement was unfair.

“It basically encourages workers from India, but does not provide the same benefit to UK citizens. This is two-tier taxes – it’s not right.”

She explained her view that that the benefits of the DCC will be “lop-sided”, claiming that the number of UK citizens working in India is not equivalent to the number of Indian citizens working in the UK.

It’s not just Badenoch who has criticised this aspect of the deal. In a post on X, Daisy Cooper MP, deputy leader of the Liberal Democrats, wrote: “This deal risks undercutting British workers at a time when they’re already being hammered by Trump’s trade war and Labour’s misguided jobs tax.”

Labour’s Reynolds dismissed these claims as “completely false”, telling BBC News: “There is no situation where I would ever tolerate British workers being undercut through any trade agreement we would sign. That is not part of the deal.”

In another interview with Sky News, Reynolds said: “This is not a tangible issue. This is the Conservative Party – and Reform – unable to accept that this Labour government has done what they couldn’t do and get this deal across the line, and inventing a false reason why they couldn’t get this deal across the line.”